All polymers begin as sunlight that falls upon the earth. Billions of years ago, some single-celled organisms captured sunlight from green chloroplast cells before dying and settling to the bottom of the ancient ocean. Later, larger multi-celled algae and zooplankton did the same, for hundreds of millions of years. Under the heat and pressure of layers of sediment and shifting continents, their carcasses became a solid substance called kerogen and, eventually, the hydrocarbon chains we’ve come to know as natural gas, petroleum, and coal.

The first modern, widely available plastic was made from nitrocellulose, a plant material, and camphor resin, a coal tar. An American inventor named John Wesley Hyatt won a prize offered by a billiard manufacturer looking for a cheaper alternative to ivory. Hyatt’s “celluloid” won with a bang, because occasionally, according to Hyatt, “the violent contact of the balls would produce a mild explosion like a percussion gun-cap.” Nitrocellulose is explosive.

The birth of plastics in the early twentieth century made possible the birth of mass-scale injection molding — shooting liquid plastic into a closed mold, letting it harden (which can take only seconds), and then opening the mold to eject the finished product. As Heather Rogers tells us in “A Brief History of Plastic” for the Brooklyn Rail, “In the mid-1930s, at one company the same worker that formerly made 350 plastic hair combs per day could turn out more than 10,000 in equal time using injection molding.”

Some long-chain hydrocarbons can and do get broken down by natural agents, such as sunlight, water, and bacteria, but those kinds of biodegradable molecules have not been the stock and trade of the plastic industry.

“The real trick is to make them stable when you’re using them, and unstable when you don’t want to use them,” explained Marc Hillmyer, who leads the Center for Sustainable Polymers at the University of Minnesota. Instead of looking for durable, long-chain molecules, chemists are now looking for short-chain molecules that can be “stitched together” for use and then “unzippered” when ready to be discarded. Xiao Zhi Lim, writing in 2018 for the New York Times, explains:

In 2016, Dr. Hillmyer and his team made a polyurethane from unzipping polymers that were chemically recyclable. Molecular units derived from sugar linked up to make the polymers, which then cross-linked into poly-urethane networks. The foam remains stable at room temperature but unzips into units if heated above 400 degrees Fahrenheit.

The economy of this approach leaves a lot to be desired because it means every polymer made this way has to go through the manufacturing process twice, first for assembly and second for disassembly. Product sales and marketing support the first stage, but what sustains the second? Even when the recovered short chains can be recombined, the cost of collection, transport, and recovery may be higher than stitching virgin polymers, and this doesn’t factor in the need to retrain a studiously nurtured throwaway culture to get in the habit of returning its discards to their source.

Ever wonder why no nuclear plants, even those that melted down at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima, have been decommissioned? It’s because the process of disassembling and downcycling their component parts is more expensive than building the plant in the first place. As we shall see, the same can be true for plastics, or not, depending on many compounding factors.

Making Plastic Precious

In late 2018, as I searched for innovative approaches to the various plastics issues, I came across a twenty-three-year-old student, Dave Hakkens, who was making YouTube tutorials and a website, Making Plastic Precious, as part of his graduation project from a design school in the Netherlands. Hakkens was showing how to recycle HDPE plastic (milk bottles, bottle tops) into craft and engineering projects (plates, furniture, roofing shingles). In a string of well-made videos, Hakkens shows how, using only simple tools, anyone can make a decent living turning waste plastic into useful things.

Hakkens and his partners provided free plans for do-it-yourself machines that could be fabricated as easily in Kenya or Nepal as in Europe or North America. Every village in the world needs a shop like his. You can see videos and download his plans to make the tools at Precious Plastic. His basic DIY setup includes the following:

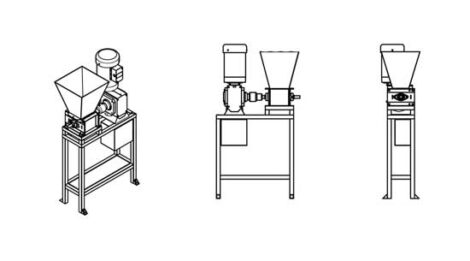

A shredder machine

Plastic waste is shredded into flakes to be used in other machines to create new things. Smaller flakes are easier to store and wash. The shredded plastic can be used as raw material for other machines or be sold back to the industry. Changing the sieve inside the shredder makes different patterns for different products. If you shred plastic by colors, you can have more control over the look and feel of your creations, adding value to the material.

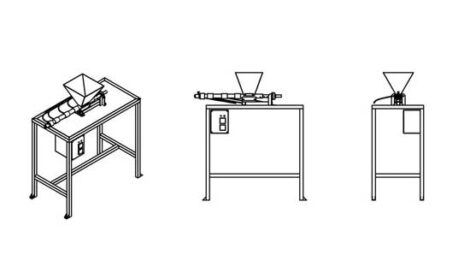

An extrusion machine

Extrusion is a continuous process in which plastic flakes move from a hopper into a flowing line that melts the flakes to mold into any shape as they harden, make 3D printing filament, or be layered in new and creative ways. This technique nicely blends differently colored plastics together and outputs a homogenous color or a smooth color gradient.

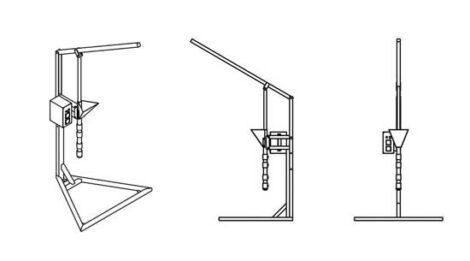

An injection machine

By injecting hot plastic flakes into a mold at high speed, you can make small objects in large volume.

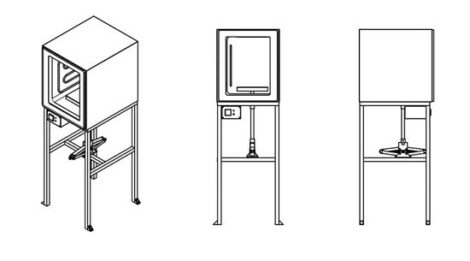

A compression machine

Something similar to an electric kitchen oven heats the plastic, which flows into a mold where a car jack is used to apply pressure. The process allows for bigger objects, such as sheets of plastic, countertops, roofing tiles, and blocks, that can be further worked on to make more complex items, such as furniture and bicycle frames. With mixes of different-colored plastics, the results look like quarried stone.

The total energy for collecting, sorting, and reprocessing one thousand pounds of postconsumer PET and HDPE is less than one-sixth as much as that required for producing virgin resin (which inherently possesses great energy content in its chemical composition). The greenhouse gas emissions from recycling, including emissions from material collection, are about one-quarter to one-third of those in virgin resin production. However, solid waste production when recycling the postconsumer materials is higher than with virgin material production because of the residuals and unusable materials produced in the sorting and reprocessing steps. Hakken’s kits have the advantage of working with clean, uniform materials. As feedstocks have to be reclaimed from mixed streams, the disadvantages increase.

One significant disadvantage is if biodegradable PLA or PHB get mixed into the feedstock stream. Since they look and weigh the same as PET and HDPE, it’s an easy mistake to make, and they can get as far as the extruder before they begin to mess up the system. Even if they melt and homogenize into the resin, after the product cools, it may be weak or inferior in other ways, or it may spontaneously disintegrate.

This is the problem when biodegradable plastic bags, cups, and similar consumer items get mixed into the recycling stream. They gum up the works. They may be nearly indistinguishable from standard PET and polyolefins to sorting equipment, but their room-temperature degradation additives can compromise the quality of the entire stream.

This is ironic because biodegradability should be our goal in developing new plastics that are ecologically benign, but it conflicts with another goal of closing the resource-to-waste cycle. Worse, many so-called biodegradable polymers require carefully controlled composting, another space-, energy-, and labor-consuming task. Those who imagine these biodegradable plastics can just be rolled out in thousands of commercial products that replace non-bio plastics are assuming that large-scale industrial composting facilities actually exist. In most municipalities, they don’t.

Another downside of bio-based polymers is that even if only 10 percent of all plastics were starch-based and derived from food crops, such as maize, soybeans, or sugarcane, it could drive up food prices, making them less affordable for the lowest-income segment of the population. Moreover, the life-cycle assessment doesn’t give them as much of a greenhouse gas advantage as you might think. Biopolymers rely on fertilizers and pesticides for feedstock production, causing N2O emissions, ozone depletion, acidification, toxicity, and eutrophication of water bodies as those agricultural chemicals leach from the soil. Chemical fertilizers give soils a short-term boost while killing them biologically over the long term, and this makes a nasty treadmill for farms that come to rely upon them. More chemicals are needed every year, while crops become weaker and sicker at the same time.

Pure traditional polymers, such as PP and PE, perform better on life-cycle analysis because of their relatively straightforward chemical processing from fossil fuels, but that is a different kind of treadmill and equally fragile in the long term. To put it simply, raw materials for producing plastics all have potential environmental impacts, whether through drilling for oil or fertilizing and harvesting crops for biofeedstock production, which currently still relies heavily on the use of fossil fuels.

For all the build-out of solar, wind, and other renewable energy sources over the past few years, the gain of energy being produced has been less than the growth in energy demand. A scientific study supported by the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure warned in December 2018 that the renewable energy industry could be about to face a fundamental obstacle: shortages in the supply of rare metals. Rare earth metals are used in solar panels and wind turbines, as well as in electric cars and consumer electronics. We don’t recycle them, and there’s not enough to meet the demand.

The same is true for plastics that derive from either fossil fuels or agricultural crops diverted from your dinner table. The day of those feedstocks is ending. It must.

Barriers

What are the barriers to recycling plastic? Along with the cleanliness and overall quality of the incoming material, plastics have several particular qualities that interfere. Plastics began their lives as organic materials broken apart in extreme conditions in laboratories or factories. They can’t just be melted or dissolved without altering their artificial molecular structure. In many cases, you have to disassemble the backbone and its dangling chain and rebuild from scratch.

Not everything is either possible or practical to recycle. Roughly half of the plastics in the municipal recycling stream are unsuitable.

Not all polymers are chemically compatible in a mixed recycling stream. Many theoretically recyclable plastics can’t be reprocessed together because they differ in melting temperature, melt viscosity, or molecular structure. Thermoformed or injection-molded products are not PE film or PS foam. Foam has its own issues because its low density makes the costs of handling and storage hard for recyclers to justify.

The recycling stream may contain plastics that have degraded from use, heat, light, or outdoor weathering. Reprocessing damages molecular properties further, so that has to be compensated for by adding new stabilizers to restore some of the lost properties.

Even within some classes, such as PET, there can be differences that frustrate recycling. Even though they are both clear packaging materials, thermoformed PET products have to be separated from the bottle PET stream because of viscosity differences, label/adhesives, additives, and sorting difficulties (thermoformed PET clamshells can be difficult to distinguish from PS, PVC, and PLA clamshells).

It is often unclear what filler or fiber an old plastic part is loaded with. A common-looking PET bottle may be blow-molded from material with multiple ethylene-vinyl alcohol barrier layers, or it may be contaminated with milk, orange juice, paint, or kerosene. Dozens of kinds of additives, mineral fillers, and reinforcing fibers can be compounded into plastics. Bales of single-polymer plastics can be contaminated with pieces of incompatible polymers, such as plastic bottle caps or lids. For these rea-sons, 40-60 percent of recycled bottle PET ends up as fibers for clothes or carpet, and well over 50 percent of HDPE food/beverage bottles are turned into non-food containers, pipes, or plastic building materials.

Which is not to say recycling is impossible. Even some of the most difficult plastics can still be downcycled. The British company Recycling Technologies makes a machine that turns plastic waste into crude oil. Scotland’s MacRebur is testing a recycled plastic road surface that is said to be stronger and more durable than asphalt roads and promises lower fuel consumption by reducing tire resistance on the road surface. The effect of plastic dust in the environment is another story, however.

More from Transforming Plastic:

Bypass plastics by shopping for reusable products in our online store:

- Bee’s Wrap Sustainable Food Storage

- Bamboo drinking straws

- Mother Earth News stainless steel drinking straws

- Bamboo Natural Home products

As a culture, we are addicted to plastic, and in today’s plastic-laden world, it is impossible to completely avoid it. Permaculturist Albert Bates addresses the magnitude and consequences of this global problem, and his evaluation is chilling to read. Trying to limit our plastic legacy can help us overcome our apathy toward this overwhelming issue, but Bates states that placing the burden entirely on consumers, as most current “solutions” do, is unfair. Bates emphasizes that the only way to stem the present onslaught is to enforce mandatory economic and industrial changes so that recycled, biosourced, and biodegradable plastic become more cost-effective than plastic made from fossil fuels. He explores current worldwide efforts for stronger regulations and better waste management, along with exciting new biological and man-made technologies for improved plastics disposal and viable alternatives. Join with Bates as an EPT (emergency planetary technician) to help everyone understand that, although our very lives are at stake, there is a promise of hope if we take action now.

Reprinted with permission from Transforming Plastic: From Pollution to Evolution by Albert Bates and published by GroundSwell Books, 2019.